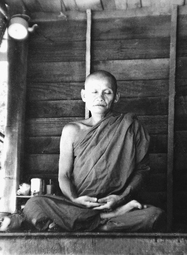

Ajahn Chah

"You are your own teacher. Looking for teachers, can't solve your own doubts. Investigate yourself to find the truth -- inside, not outside. Knowing yourself is most important."

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Biography

Venerable Ajahn Chah was born on June 17, 1918 in a small village near the town of Ubon Ratchathani, North-East Thailand. After finishing his basic schooling, he spent three years as a novice before returning to lay life to help his parents on the farm. At the age of twenty, however, he decided to resume monastic life, and on April 26, 1939 he received upasampadā (bhikkhu ordination). Ajahn Chah’s early monastic life followed a traditional pattern, of studying Buddhist teachings and the Pali scriptural language. In his fifth year his father fell seriously ill and died, a blunt reminder of the frailty and precariousness of human life. It caused him to think deeply about life’s real purpose, for although he had studied extensively and gained some proficiency in Pali, he seemed no nearer to a personal understanding of the end of suffering. Feelings of disenchantment set in, and finally, in 1946 he abandoned his studies and set off on mendicant pilgrimage.

He walked some 400 km to Central Thailand, sleeping in forests and gathering almsfood in the villages on the way. He took up residence in a monastery where the vinaya, (monastic discipline), was carefully studied and practised. While there he was told about Venerable Ajahn Mun Bhuridatta, a most highly respected meditation master. Keen to meet such an accomplished teacher, Ajahn Chah set off on foot for the Northeast in search of him.

At this time Ajahn Chah was wrestling with a crucial problem. He had studied the teachings on morality, meditation and wisdom, which the texts presented in minute and refined detail, but he could not see how they could actually be put into practice. Ajahn Mun told him that although the teachings are indeed extensive, at their heart they are very simple. With mindfulness established, if it is seen that everything arises in the heart-mind, right there is the true path of practice. This succinct and direct teaching was a revelation for Ajahn Chah, and transformed his approach to practice. The Way was clear.

For the next seven years Ajahn Chah practiced in the style of the austere Forest Tradition, wandering through the countryside in quest of quiet and secluded places for developing meditation. He lived in tiger and cobra infested jungles, using reflections on death to penetrate to the true meaning of life. On one occasion he practised in a cremation ground, to challenge and eventually overcome his fear of death. While he was in the cremation ground, a rainstorm left him cold and drenched, and he faced the utter desolation and loneliness of a wandering homeless monk.

In 1954, after years of wandering, he was invited back to his home village. He settled close by, in a fever ridden, haunted forest called ‘Pah Pong’. Despite the hardships of malaria, poor shelter and sparse food, disciples gathered around him in increasing numbers. This was the beginning of the first monastery in the Ajahn Chah tradition, Wat Pah Pong. With time branch monasteries were established at other locations.

In 1967 an American monk came to stay at Wat Pah Pong. The newly ordained Venerable Sumedho had just spent his first Vassa (‘Rains’ retreat) practicing intensive meditation at a monastery near the Laotian border. Although his efforts had borne some fruit, Venerable Sumedho realized that he needed a teacher who could train him in all aspects of monastic life. By chance, one of Ajahn Chah’s monks, one who happened to speak a little English, visited the monastery where Venerable Sumedho was staying. Upon hearing about Ajahn Chah, he asked to take leave of his preceptor, and went back to Wat Pah Pong with the monk. Ajahn Chah willingly accepted the new disciple, but insisted that he receive no special allowances for being a Westerner. He would have to eat the same simple almsfood and practice in the same way as any other monk at Wat Pah Pong. The training there was quite harsh and forbidding. Ajahn Chah often pushed his monks to their limits, to test their powers of endurance so that they would develop patience and resolution. He sometimes initiated long and seemingly pointless work projects, in order to frustrate their attachment to tranquility. The emphasis was always on surrendering to the way things are, and great stress was placed upon strict observance of the vinaya.

In the course of events, other Westerners came through Wat Pah Pong. By the time Venerable Sumedho was a bhikkhu of five vassas, and Ajahn Chah considered him competent enough to teach, some of these new monks had also decided to stay on and train there. In the hot season of 1975, Venerable Sumedho and a handful of Western bhikkhus spent some time living in a forest not far from Wat Pah Pong. The local villagers there asked them to stay on, and Ajahn Chah consented. The Wat Pah Nanachat (‘International Forest Monastery’) came into being, and Venerable Sumedho became the abbot of the first monastery in Thailand to be run by and for English-speaking monks.

In 1977, Ajahn Chah was invited to visit Britain by the English Sangha Trust, a charity with the aim of establishing a locally-resident Buddhist Sangha. He took Venerable Sumedho and Venerable Khemadhammo along to England. Seeing the serious interest there, he left them in London at the Hampstead Vihara, with two of his other Western disciples who were then visiting Europe. He returned to Britain in 1979, at which time the monks were leaving London to begin Chithurst Buddhist Monastery in Sussex. He then went on to America and Canada to visit and teach. After this trip, and again in 1981, Ajahn Chah spent the ‘Rains’ away from Wat Pah Pong, since his health was failing due to the debilitating effects of diabetes. As his illness worsened, he would use his body as a teaching, a living example of the impermanence of all things. He constantly reminded people to endeavor to find a true refuge within themselves, since he would not be able to teach for very much longer. Before the end of the ‘Rains’ of 1981, he was taken to Bangkok for an operation. However, the procedure did little to improve his condition.

Within a few months he stopped talking, and gradually he lost control of his limbs until he was virtually paralyzed and bedridden. From then on, he was diligently and lovingly nursed and attended by devoted disciples, grateful for the occasion to offer service to the teacher who so patiently and compassionately showed the Way to so many.

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Ajahn Chah (b. June 17, 1918, Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand – d. January 16, 1992, Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand) was a Thai Buddhist monk. He was an influential teacher of the Buddhadhamma and a founder of two major monasteries in the Thai Forest Tradition.

Respected and loved in his own country as a man of great wisdom, he was also instrumental in establishing Theravada Buddhism in the West. Beginning in 1979 with the founding of Cittaviveka (commonly known as Chithurst Buddhist Monastery)[1] in the United Kingdom, the Forest Tradition of Ajahn Chah has spread throughout Europe, the United States and the British Commonwealth. The dhamma talks of Ajahn Chah have been recorded, transcribed and translated into several languages.

More than one million people, including the Thai royal family, attended Ajahn Chah's funeral in January 1993[2] held a year after his death due to the "hundreds of thousands of people expected to attend".[3] He left behind a legacy of dhamma talks, students, and monasteries.

Ajahn Chah (Thai: อาจารย์ชา) was also commonly known as Luang Por Chah (Thai: หลวงพ่อชา). His birth name was Chah Chuangchot (Thai: ชา ช่วงโชติ),[4]: 21 his Dhamma name was Subhaddo (Thai: สุภทฺโท),[4]: 38 and his monastic title was Phra Bodhiñāṇathera (Thai: พระโพธิญาณเถร).[4]: 184 [5]

Ajahn Chah was born on June 17, 1918, near Ubon Ratchathani in the Isan region of northeast Thailand. His family were subsistence farmers. As is traditional, Ajahn Chah entered the monastery as a novice at the age of nine, where, during a three-year stay, he learned to read and write. The definitive 2017 biography of Ajahn Chah Stillness Flowing[4] states that Ajahn Chah took his novice vows in March 1931 and that his first teacher as a novice was Ajahn Lang. He left the monastery to help his family on the farm, but later returned to monastic life on April 16, 1939, seeking ordination as a Theravadan monk (or bhikkhu).[6] According to the book Food for the Heart: The Collected Writings of Ajahn Chah, he chose to leave the settled monastic life in 1946 and became a wandering ascetic after the death of his father.[6] He walked across Thailand, taking teachings at various monasteries. Among his teachers at this time was Ajahn Mun, a renowned meditation master in the Forest Tradition. Ajahn Chah lived in caves and forests while learning from the meditation monks of the Forest Tradition. A website devoted to Ajahn Chah describes this period of his life:

During the early part of the twentieth century Theravada Buddhism underwent a revival in Thailand under the leadership of teachers whose intentions were to raise the standards of Buddhist practise throughout the country. One of these teachers was Ajahn Mun. Ajahn Chah continued Ajahn Mun's high standards of practice when he became a teacher.[7]

The monks of this tradition keep very strictly what they believe to be the original monastic rule laid down by the Buddha known as the vinaya. The early major schisms in the Buddhist sangha were largely due to disagreements over which set of training rules should be applied. Some adopted a more flexible set, whereas others adopted a more strict one, both sides believing to follow the rules as the Buddha had framed them. The Theravada tradition is the heir to the latter view. An example of the strictness of the discipline might be the rule regarding eating: they uphold the rule to only eat between dawn and noon. In the Thai Forest Tradition, monks and nuns go further and observe the 'one eaters practice', whereby they only eat one meal during the morning. This special practice is one of the thirteen dhutanga, optional ascetic practices permitted by the Buddha that are used on an occasional or regular basis to deepen meditation practice and promote contentment with subsistence. Other examples of these practices are sleeping outside under a tree or dwelling in secluded forests or graveyards.

After years of wandering, Ajahn Chah decided to plant roots in an uninhabited grove near his birthplace. In 1954, Wat Nong Pah Pong monastery was established, where Ajahn Chah could teach his simple, practice-based form of meditation. He attracted a wide variety of disciples, which included, in 1966, the first Westerner, Venerable Ajahn Sumedho.[6] Wat Nong Pah Pong [8] includes over 250 branches throughout Thailand, as well as over 15 associated monasteries and ten lay practice centers around the world.[6]

In 1975, Wat Pah Nanachat (International Forest Monastery) was founded with Ajahn Sumedho as the abbot. Wat Pah Nanachat was the first monastery in Thailand specifically geared towards training English-speaking Westerners in the monastic Vinaya, as well as the first run by a Westerner.

In 1977, Ajahn Chah and Ajahn Sumedho were invited to visit the United Kingdom by the English Sangha Trust who wanted to form a residential sangha.[9] 1979 saw the founding of Cittaviveka (commonly known as Chithurst Buddhist Monastery due to its location in the small hamlet of Chithurst) with Ajahn Sumedho as its head. Several of Ajahn Chah's Western students have since established monasteries throughout the world.

By the early 1980s, Ajahn Chah's health was in decline due to diabetes. He was taken to Bangkok for surgery to relieve paralysis caused by the diabetes, but it was to little effect. Ajahn Chah used his ill health as a teaching point, emphasizing that it was "a living example of the impermanence of all things...(and) reminded people to endeavor to find a true refuge within themselves, since he would not be able to teach for very much longer".[6] Ajahn Chah would remain bedridden and ultimately unable to speak for ten years, until his death on January 16, 1992, at the age of 73.[10][3]

- Ajahn Sumedho, founder and former abbot of Chithurst Buddhist Monastery and Amaravati Buddhist Monastery, Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire, England

- Ajahn Khemadhammo, abbot of The Forest Hermitage, Warwickshire, England

- Ajahn Viradhammo, abbot of Tisarana Buddhist Monastery in Perth, Ontario, Canada

- Ajahn Sucitto, retired abbot of Cittaviveka monastery. A Dhamma writer.

- Ajahn Pasanno, abbot of Abhayagiri Monastery, Redwood Valley, California, USA

- Ajahn Amaro, abbot of Amaravati Monastery, Amaravati Buddhist Monastery, Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire England

- Ajahn Brahmavamso, abbot of Bodhinyana Monastery, Perth, Western Australia

- Ajahn Jayasaro, author of Stillness Flowing, the biography of Ajahn Chah, and former abbot of Wat Pah Nanachat

- Jack Kornfield, co-founder of Insight Meditation Society, Barre, Massachusetts, USA and Spirit Rock Meditation Center in Woodacre, California, USA

- Still Flowing Water: Eight Dhamma Talks (Thanissaro Bhikkhu, ed.). Metta Forest Monastery (2007).

- The Path to Peace. The Sangha, Wat Pah Nanachat (1996).

- Clarity of Insight. The Sangha, Wat Pah Nanachat (2000).

- A Still Forest Pool: The Insight Meditation of Achaan Chah (Jack Kornfield ed.). Theosophical Publishing House (1985). ISBN 0-8356-0597-3.

- Being Dharma: The Essence of the Buddha's Teachings. Shambahla Press, 2001. ISBN 1-57062-808-4.

- Food for the Heart (Ajahn Amaro, ed.). Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2002. ISBN 0-86171-323-0.

- Everything Is Teaching Us. Amaravati Publications, 2018. ISBN 978-1-78432-106-2.

- Living Dhamma. Amaravati Publications, 2018. ISBN 978-1-78432-099-7.

- A Taste of Freedom. Amaravati Publications, 2018. ISBN 978-1-78432-098-0.

- On Meditation. Amaravati Publications, 2018. ISBN 978-1-78432-101-7

- Bodhinyana. Amaravati Publications, 2018.ISBN 978-1-78432-097-3

- Meditation: A Collection of Talks on Cultivating the Mind

- The Training Of The Heart (BL107)

- Our Real Home (BL111)

- ^ Website of Chithurst Buddhist Monastery

- ^ "The State Funeral of Luang Por Chah". Ajahn Sucitto. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Ajahn Chah Passes Away". Forest Sangha Newsletter. April 1992. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d Ajahn Jayasāro (2017). Stillness Flowing: The Life and Teachings of Ajahn Chah (PDF). Bangkok: Panyaprateep Foundation. ISBN 978-616-7930-09-1.

- ^ "แจ้งความสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี เรื่อง พระราชทานสัญญาบัตรตั้งสมณศักดิ์" (PDF). Royal Gazette. Vol. 90, no. 177. 28 December 1973. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f "Biography of Ajahn Chah". Wat Nong Pah Pong. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ Wat Nong Pah Pong. "A Collection of Dhammatalks by Ajahn Chah". Everything Is Teaching Us. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Website of Wat Nong Pah Pong". Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ "Ajahn Sumedho (1934-)". BuddhaNet. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ "Ajahn Chah: biography". Forest Sangha. Retrieved 18 March 2016.