Dalai Lama (Tenzin Gyatso)

"My religion is kindness." (01/17/2022)

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

| Dalai Lama | |

|---|---|

| ཏཱ་ལའི་བླ་མ་ | |

| Residence |

|

| Formation | 1391 |

| First holder | Gendün Drubpa, 1st Dalai Lama, posthumously awarded after 1578. |

| Website | dalailama |

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

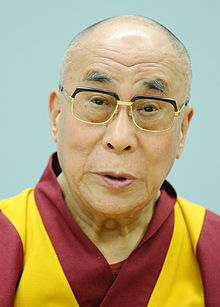

14th Dalai Lama (born July 6, 1935, Taktser, Tibet) is the title of the Tibetan Buddhist monk Tenzin Gyatso, the first Dalai Lama to become a global figure, largely for his advocacy of Buddhism and of the rights of the people of Tibet. Despite his fame, he dispensed with much of the pomp surrounding his office, describing himself as a “simple Buddhist monk.” Having fled Tibet in 1959, he took up residence in Dharmshala, India, where he led the Tibetan Buddhist community in exile. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1989.

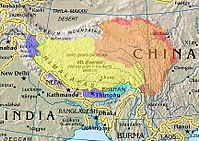

It is a tenet of Tibetan Buddhism (which traditionally has flourished not only in Tibet but also in Mongolia, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan, and other parts of India and China) that highly advanced religious teachers return to the world after their death, motivated by their compassion for the world. At the time of the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950, there were several thousand of these teachers, often referred to in English as “incarnate lamas” (the term in Tibetan is sprul sku, also transliterated as tulku, which literally means “emanation body”). The most important and famous of these teachers was the Dalai Lama, whose line began in the 14th century. The third incarnation of this figure, named Bsod-nams-rgya-mtsho (Sonam Gyatso) (1543–88), was given the title of Dalai Lama (“Ocean Teacher”) by the Mongol chieftain Altan Khan in 1580. The two previous incarnations were posthumously designated as the first and second Dalai Lamas. Until the 17th century the Dalai Lamas were prominent religious teachers of the Dge-lugs-pa (Gelukpa; also called Yellow Hats) sect, one of the four major sects of Tibetan Buddhism.

In 1642 the 5th Dalai Lama was given temporal control of Tibet, and the Dalai Lamas remained head of state there until the flight of the 14th Dalai Lama into exile in 1959. It is said that the incarnations prior to the 14th Dalai Lama extend not only to the previous 13 but further back into Tibetan history to include the first Buddhist kings (chos rgyal) of the 7th, 8th, and 9th centuries. All the Dalai Lamas and these early kings are considered human embodiments of Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva (buddha-to-be) of compassion and the protector of Tibet.

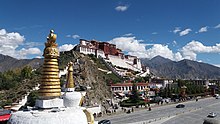

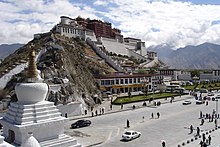

Previous Dalai Lamas were often figures cloaked in mystery, living in isolation in the Potala Palace in Lhasa, the capital of Tibet. In contrast, the 14th Dalai Lama achieved a level of visibility and celebrity that would have been unimaginable for his predecessors. He became the most famous Buddhist teacher in the world, widely respected for his commitment both to nonviolence and to the cause of Tibetan freedom. The 14th Dalai Lama has traveled the globe, spreading notions of peace and Buddhist ideas. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1989, the Templeton Prize in 2012, and countless other accolades along with achieving global popular recognition as an influential religious leader and thinker in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Early life in Tibet

The 14th Dalai Lama’s flight from Tibet

After they took control of China in 1949, the communists asserted that Tibet was part of the “Chinese motherland” (the non-Chinese Qing rulers of China had exercised suzerainty over the region from the 18th century until the dynasty’s fall in 1911/12), and Chinese cadres entered Tibet in 1950. With a crisis looming, the Dalai Lama was asked to assume the role of head of state, which he did on November 17, 1950, at the age of 15. Attempts by the Chinese to collectivize monastic properties in eastern Tibet met with resistance, which led to violence and intervention by the People’s Liberation Army that year. On May 23, 1951, a Tibetan delegation in Beijing signed (under duress) a “Seventeen-Point Agreement,” thereby ceding control of Tibet to China; Chinese troops marched into Lhasa on September 9. During the next seven and a half years, the young Dalai Lama sought to protect the interests of the Tibetan people, departing for China in 1954 for a year-long tour, during which he met with China’s leader, Mao Zedong.

In 1956 the Dalai Lama traveled to India to participate in the celebration of the 2,500th anniversary of the Buddha’s Enlightenment. Against the advice of some members of his circle, he returned to Tibet, where the situation continued to deteriorate. Guerrillas fought Chinese troops in eastern Tibet, and a significant number of refugees flowed into the capital. In February 1959, despite the turmoil, the Dalai Lama sat for his examination for the rank of geshe (“spiritual friend”), the highest scholastic achievement in the Dge-lugs-pa sect.

As tensions continued to escalate, rumors that Chinese authorities planned to kidnap the Dalai Lama led to a popular uprising in Lhasa on March 10, 1959, during which crowds surrounded the Dalai Lama’s summer palace to protect him. The unrest caused a breakdown in communications between the Dalai Lama’s government and Chinese military authorities, and during the chaos, the Dalai Lama (disguised as a Tibetan soldier) escaped under cover of darkness on March 17. Accompanied by a small party of his family and teachers and escorted by guerrilla fighters, the Dalai Lama made his way on foot and horseback across the Himalayas, pursued by Chinese troops. On March 31 he and his escorts arrived in India, where the Indian government offered them asylum.

Later life in exile of the 14th Dalai Lama

In the wake of the Lhasa uprising and the Chinese consolidation of power across Tibet, tens of thousands of Tibetans followed the Dalai Lama into exile. In 1960 he established his government-in-exile in Dharmshala, a former British hill station in the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh, where he continued to reside. The government of India, however, was reluctant to allow all the Tibetan refugees to concentrate in one region, and thus it created settlements across the subcontinent where asylum-seeking Tibetans established farming communities and built monasteries. The welfare of the refugees and the preservation of Tibetan culture in exile, especially in light of reports of the systematic destruction of Tibetan institutions during China’s Cultural Revolution (1966–76), were the primary concerns of the Dalai Lama during this period.

The Dalai Lama traveled little during the early part of his exile and published only two books, an introduction to Buddhism and an autobiography. In later years, however, he traveled quite extensively, visiting Europe for the first time in 1973 and the United States for the first time in 1979. He subsequently traveled to dozens of other countries, delivering addresses at colleges and universities, meeting with political and religious leaders, and lecturing on Buddhism.

The 14th Dalai Lama’s politics and philosophy

The Dalai Lama’s activities have focused on both political matters concerning Tibet and wider philosophical matters on Buddhism and religion in the modern world.

He has worked extensively to build and sustain international awareness of the plight of Tibet. In 1987 he put forth his “Five Point Peace Plan” at the U.S. Congressional Human Rights Caucus. In that plan, he called for the

In 1988, at a session of the European Parliament in Strasbourg, France, the Dalai Lama set forth a plan that he termed the “Middle Way Approach,” in which Tibet would be an autonomous region of China rather than an independent state. He continued to advocate this approach between the complete independence of Tibet and its complete absorption into the People’s Republic of China. A significant component of his plan would be to maintain Tibet’s autonomy while allowing for the region to benefit from Chinese technological and defense prowess. In addition, the Dalai Lama sent numerous delegations to China to discuss such proposals, but they met with little success. In recognition of his efforts, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1989.

Related to his peace efforts, interreligious harmony frequently featured in his advocacy. In his essay “A Human Approach to World Peace” he wrote

Interfaith understanding will bring about the unity necessary for all religions to work together. However, although this is indeed an important step, we must remember that there are no quick or easy solutions. We cannot hide the doctrinal differences that exist among various faiths, nor can we hope to replace the existing religions by a new universal belief. Each religion has its own distinctive contributions to make, and each in its own way is suitable to a particular group of people as they understand life. The world needs them all.

The Dalai Lama’s other main goal has been to disseminate the central tenets of Buddhism to a wide audience around the globe. During his tenure, he presided over 34 Kalachakra (Wheel of Time) initiations worldwide. He authored more than a hundred books on Buddhist themes, many of which were derived from public lectures or interviews. Some of these works were written in the traditional form of commentaries on Buddhist scriptures, while others ranged more widely over topics such as interreligious dialogue and the compatibility of Buddhism and science.

On the subject of Buddhism and science, Tenzin Gyatso wrote extensively. Describing himself as “half Buddhist monk, half scientist,” he included in his books numerous conversations with scientists. In his 2005 book The Universe in a Single Atom: The Convergence of Science and Spirituality, the Dalai Lama offered a personal and analytical reconciliation of religion and science. In his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1989, he pivoted from a larger conversation about avoiding violence to unifying science and religion:

With the ever-growing impact of science on our lives, religion and spirituality have a greater role to play by reminding us of our humanity. There is no contradiction between the two. Each gives us valuable insights into the other. Both science and the teachings of the Buddha tell us of the fundamental unity of all things. This understanding is crucial if we are to take positive and decisive action on the pressing global concern with the environment. I believe all religions pursue the same goals, that of cultivating human goodness and bringing happiness to all human beings. Though the means might appear different, the ends are the same.

Writing for The New York Times in 2005, he suggested

If science proves some belief of Buddhism wrong, then Buddhism will have to change. In my view, science and Buddhism share a search for the truth and for understanding reality. By learning from science about aspects of reality where its understanding may be more advanced, I believe that Buddhism enriches its own worldview.

Since a Dalai Lama is considered the incarnation of Avalokiteshvara (“the One Who Looks Down”), the bodhisattva of compassion, it is not surprising that compassion is a main theme in the Dalai Lama’s extensive writing on Buddhist ideas. Avalokiteshvara—in Tibetan, Chenrezig (“All-Seeing Eye”)—is notable for having taken the quintessential bodhisattva vow to assist every sentient being on earth to achieve release (moksha) from suffering (dukkha) prior to achieving his own release and status of buddhahood. Writing for Encyclopædia Britannica, the Dalai Lama contended that there is a feedback loop of helping others, since “compassion makes us happy!”

Throughout his life, the Dalai Lama has fulfilled his traditional roles for the Tibetan community: he is revered by Tibetans both in Tibet and in exile as the human incarnation of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara and as the protector of the Tibetan people. In the latter role, he consulted with oracles in making major decisions and made pronouncements on the practice of Tibetan Buddhism, as in 1980 and again in 1996, when he spoke out against the propitiation of the wrathful deity Dorje Shugden, one of the protectors of the Dge-lugs-pa (Gelukpa) sect. He also has a significant following among Tibetan Buddhist followers in Mongolia, who make up about half the country’s population. In that role, he advised Mongolians against drinking alcohol in favor of drinking horse milk, and in 2023 he recognized a United States-born boy as the latest reincarnation of Jebtsundamba Khutugtu, the head of Tibetan Buddhism in Mongolia.

The 14th Dalai Lama’s uncertain succession

After the Dalai Lama reached the age of 70, the question of his successor was repeatedly raised. In the 1980s his public speculation about whether there would be a need for another Dalai Lama was taken by some as a call to the Tibetan community to preserve its culture in exile. In 1995 the Dalai Lama played a role in recognizing the 11th Panchen Lama—an important religious leader in Tibetan Buddhism who is in turn responsible for helping recognize the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama. The Dalai Lama’s choice, Gedhun Choekyi Nyima, and his family were detained by the Chinese government and have since been missing, according to authorities outside China (China insists that he and his family are living a normal life in Tibet). Later in 1995 the Chinese government appointed its own choice for the Panchen Lama, Gyancain Norbu.

In a 2004 interview with Time magazine, the 14th Dalai Lama stated that if Tibetans want a 15th Dalai Lama, there will be one, and the successor would be discovered not in Chinese-controlled Tibet but in exile, thus possibly suggesting a way of avoiding Chinese oversight. In 2007 the Chinese communist government declared that it would have final say over Tibetan Buddhist lamas’ reincarnations and prohibited anyone outside the country (including the present Dalai Lama) from having any involvement. Yet the Dalai Lama cautioned against political involvement in the process of finding the incarnation, and he subsequently suggested that he himself might appoint his successor. The Chinese government rejected this idea and insisted that the tradition of selecting a new Dalai Lama by determining the reincarnation of the predecessor had to be maintained. Some observers speculated that two Dalai Lamas, one in exile and one in China, might be identified, following the example of the Panchen Lama’s selection in 1995. In 2007 the 14th Dalai Lama suggested that his successor could be a woman, breaking with a long tradition of male lamas.

In 2011 the Dalai Lama stepped down as the political head of the Tibetan government-in-exile, but he remained as the community’s religious leader. The temporal role of tending to the Tibetan people, he decided, would be handled by a democratically elected body. In his retirement speech, he declared that “the rule by kings and religious figures is outdated. We have to follow the trend of the free world, which is that of democracy.” In making this decision, he ended the political authority of the Dalai Lama, which had begun with the fifth Dalai Lama in the 17th century and made the role solely religious.

The 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso,[b] full spiritual name: Jetsun Jamphel Ngawang Lobsang Yeshe Tenzin Gyatso, also known as Tenzin Gyatso;[c] né Lhamo Thondup;[d] is the incumbent Dalai Lama, the highest spiritual leader and head of Tibetan Buddhism. Before 1959, he served as both the resident spiritual and temporal leader of Tibet, and subsequently established and led the Tibetan government in exile represented by the Central Tibetan Administration in Dharamsala, India.[2][3] The adherents of Tibetan Buddhism consider the Dalai Lama a living Bodhisattva, specifically an emanation of Avalokiteśvara (in Sanskrit) or Chenrezig (in Tibetan), the Bodhisattva of Compassion, a belief central to the Tibetan Buddhist tradition and the institution of the Dalai Lama. The Dalai Lama, whose name means Ocean of Wisdom, is known to Tibetans as Gyalwa Rinpoche, The Precious Jewel-like Buddha-Master, Kundun, The Presence, and Yizhin Norbu, The Wish-Fulfilling Gem. His devotees, as well as much of the Western world, often call him His Holiness the Dalai Lama, the style employed on his website. He is also the leader and a monk of the Gelug school, the newest school of Tibetan Buddhism, formally headed by the Ganden Tripa.[4]

The 14th Dalai Lama was born to a farming family in Taktser (Hongya Village), in the traditional Tibetan region of Amdo, at the time a Chinese frontier district.[5][6][7][8] He was selected as the tulku of the 13th Dalai Lama in 1937, and formally recognized as the 14th Dalai Lama in 1939.[9] As with the recognition process for his predecessor, a Golden Urn selection process was waived and approved by the Central Government of the Republic of China.[10][11][12][13] His enthronement ceremony was held in Lhasa on 22 February 1940.[9] At the time of his selection, a form of Tibetan government called Ganden Phodrang administered the traditional Tibetan regions of Ü-Tsang, Kham and Amdo.[14] As Chinese forces re-entered and annexed Tibet, Ganden Phodrang invested the Dalai Lama with temporal duties on 17 November 1950 (at 15 years of age) until his exile in 1959.[15][16]

During the 1959 Tibetan uprising, the Dalai Lama escaped to India, where he continues to live. On 29 April 1959, the Dalai Lama established the independent Tibetan government in exile in the north Indian hill station of Mussoorie, which then moved in May 1960 to Dharamshala, where he resides. He retired as political head in 2011 to make way for a democratic government, the Central Tibetan Administration.[17][18][19][20] The Dalai Lama advocates for the welfare of Tibetans and since the early 1970s has called for the Middle Way Approach with China to peacefully resolve the issue of Tibet.[21] This policy, adopted democratically by the Central Tibetan Administration and the Tibetan people through long discussions, seeks to find a middle ground, "a practical approach and mutually beneficial to both Tibetans and Chinese, in which Tibetans can preserve their culture and religion and uphold their identity," and China's assertion of sovereignty over Tibet, aiming to address the interests of both parties through dialogue and communication and for Tibet to remain a part of China.[22][23][24]

The Dalai Lama travels worldwide to give Tibetan Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism teachings, and his Kalachakra teachings and initiations are international events. He also attends conferences on a wide range of subjects, including the relationship between religion and science, meets with other world leaders, religious leaders, philosophers, and scientists, online and in-person. His work includes focus on the environment, economics, women's rights, nonviolence, interfaith dialogue, physics, astronomy, Buddhism and science, cognitive neuroscience,[25][26] reproductive health and sexuality. The Dalai Lama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989. Time magazine named the Dalai Lama Gandhi's spiritual heir to nonviolence.[27][28] The 12th General Assembly of the Asian Buddhist Conference for Peace in New Delhi unanimously recognized the Dalai Lama's contributions to global peace, his lifelong efforts in uniting Buddhist communities worldwide, and bestowed upon him the title of “Universal Supreme Leader of the Buddhist World.” They also designated 6 July, his birthday, as the Universal Day of Compassion.[29][30]

Early life and background

[edit]Lhamo Thondup[31] was born on 6 July 1935 to a farming and horse trading family in the small hamlet of Taktser,[e] or Chija Tagtser,[36][f] at the edge of the traditional Tibetan region of Amdo in Qinghai Province.[32]

He was one of seven siblings to survive childhood and one of the three supposed reincarnated Rinpoches in the same family. His eldest sister Tsering Dolma, was 16 years his senior and was midwife to his mother at his birth.[37] She would accompany him into exile and found Tibetan Children's Villages.[38] His eldest brother, Thupten Jigme Norbu, had been recognised at the age of three by the 13th Dalai Lama as the reincarnation of the high Lama, the 6th Taktser Rinpoche.[39] His fifth brother, Tendzin Choegyal, had been recognised as the 16th Ngari Rinpoche.[citation needed] His sister, Jetsun Pema, spent most of her adult life on the Tibetan Children's Villages project.[citation needed] The Dalai Lama has said that his first language was "a broken Xining language which was (a dialect of) the Chinese language," a form of Central Plains Mandarin, and his family speak neither Amdo Tibetan nor Lhasa Tibetan.[40][41][42]

After the demise of the 13th Dalai Lama, in 1935, the Ordinance of Lama Temple Management[g][43][44] was published by the Central Government. In 1936, the Method of Reincarnation of Lamas[h][45][46] was published by the Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission of the Central Government. Article 3 states that death of lamas, including the Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama, should be reported to the commission, soul boys should be located and checked by the commission, and a lot-drawing ceremony with the Golden Urn system should be held. Article 6 states that local governments should invite officials from the Central Government to take care of the sitting-in-the-bed ceremony. Article 7 states that soul boys should not be sought from current lama families. This article echoes what the Qianlong Emperor described in The Discourse of Lama to eliminate greedy families with multiple reincarnated rinpoches, lamas.[47] Based on custom and regulation, the regent was actively involved in the search for the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama.

Following reported signs and visions, three search teams were sent out to the north-east, the east, and the south-east to locate the new incarnation when the boy who was to become the 14th Dalai Lama was about two years old.[48] Sir Basil Gould, British delegate to Lhasa in 1936, related his account of the north-eastern team to Sir Charles Alfred Bell, former British resident in Lhasa and friend of the 13th Dalai Lama. Among other omens, the head of the embalmed body of the 13th Dalai Lama, at first facing south-east, had turned to face the north-east, indicating, it was interpreted, the direction in which his successor would be found. The Regent, Reting Rinpoche, shortly afterwards had a vision at the sacred lake of Lhamo La-tso which he interpreted as Amdo being the region to search. This vision was also interpreted to refer to a large monastery with a gilded roof and turquoise tiles, and a twisting path from there to a hill to the east, opposite which stood a small house with distinctive eaves. The team, led by Kewtsang Rinpoche, went first to meet the Panchen Lama, who had been stuck in Jyekundo, in northern Kham.[48]

The Panchen Lama had been investigating births of unusual children in the area ever since the death of the 13th Dalai Lama.[49] He gave Kewtsang the names of three boys whom he had discovered and identified as candidates. Within a year the Panchen Lama had died. Two of his three candidates were crossed off the list but the third, a "fearless" child, the most promising, was from Taktser village, which, as in the vision, was on a hill, at the end of a trail leading to Taktser from the great Kumbum Monastery with its gilded, turquoise roof. There they found a house, as interpreted from the vision—the house where Lhamo Dhondup lived.[48][49]

The 14th Dalai Lama claims that at the time, the village of Taktser stood right on the "real border" between the region of Amdo and China.[50] According to the search lore, when the team visited, posing as pilgrims, its leader, a Sera Lama, pretended to be the servant and sat separately in the kitchen. He held an old mala that had belonged to the 13th Dalai Lama, and the boy Lhamo Dhondup, aged two, approached and asked for it. The monk said "if you know who I am, you can have it." The child said "Sera Lama, Sera Lama" and spoke with him in a Lhasa accent, in a dialect the boy's mother could not understand. The next time the party returned to the house, they revealed their real purpose and asked permission to subject the boy to certain tests. One test consisted of showing him various pairs of objects, one of which had belonged to the 13th Dalai Lama and one which had not. In every case, he chose the Dalai Lama's own objects and rejected the others.[51]

From 1936 the Hui 'Ma Clique' Muslim warlord Ma Bufang ruled Qinghai as its governor under the nominal authority of the Republic of China central government.[52] According to an interview with the 14th Dalai Lama, in the 1930s, Ma Bufang had seized this north-east corner of Amdo in the name of Chiang Kai-shek's weak government and incorporated it into the Chinese province of Qinghai.[53] Before going to Taktser, Kewtsang had gone to Ma Bufang to pay his respects.[49] When Ma Bufang heard a candidate had been found in Taktser, he had the family brought to him in Xining.[54] He first demanded proof that the boy was the Dalai Lama, but the Lhasa government, though informed by Kewtsang that this was the one, told Kewtsang to say he had to go to Lhasa for further tests with other candidates. They knew that if he was declared to be the Dalai Lama, the Chinese government would insist on sending a large army escort with him, which would then stay in Lhasa and refuse to budge.[55]

Ma Bufang, together with Kumbum Monastery, then refused to allow him to depart unless he was declared to be the Dalai Lama, but withdrew this demand in return for 100,000 Chinese dollars ransom in silver to be shared among them, to let them go to Lhasa.[55][56] Kewtsang managed to raise this, but the family was only allowed to move from Xining to Kumbum when a further demand was made for another 330,000 dollars ransom: 100,000 each for government officials, the commander-in-chief, and the Kumbum Monastery; 20,000 for the escort; and only 10,000 for Ma Bufang himself, he said.[57]

Two years of diplomatic wrangling followed before it was accepted by Lhasa that the ransom had to be paid to avoid the Chinese getting involved and escorting him to Lhasa with a large army.[58] Meanwhile, the boy was kept at Kumbum where two of his brothers were already studying as monks and recognised incarnate lamas.[59] The payment of 300,000 silver dollars was then advanced by Muslim traders en route to Mecca in a large caravan via Lhasa. They paid Ma Bufang on behalf of the Tibetan government against promissory notes to be redeemed, with interest, in Lhasa.[59][60] The 20,000-dollar fee for an escort was dropped, since the Muslim merchants invited them to join their caravan for protection; Ma Bufang sent 20 of his soldiers with them and was paid from both sides since the Chinese government granted him another 50,000 dollars for the expenses of the journey. Furthermore, the Indian government helped the Tibetans raise the ransom funds by affording them import concessions.[60]

On 22 September 1938, representatives of Tibet Office in Beijing informed Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission that 3 candidates were found and ceremony of Golden Urn would be held in Tibet.[61]

In October 1938, the Method of Using Golden Urn for the 14th Dalai Lama was drafted by Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission.[62]

On 12 December 1938, regent Reting Rinpoche informed Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission that three candidates were found and ceremony of Golden Urn would be held.[63]

Released from Kumbum, on 21 July 1939 the party travelled across Tibet on a journey to Lhasa in the large Muslim caravan with Lhamo Dhondup, now four years old, riding with his brother Lobsang in a special palanquin carried by two mules, two years after being discovered. As soon as they were out of Ma Bufang's area, he was officially declared to be the 14th Dalai Lama by the Kashag, and after ten weeks of travel he arrived in Lhasa on 8 October 1939.[64] The ordination (pabbajja) and giving of the monastic name of Tenzin Gyatso were arranged by Reting Rinpoche and according to the Dalai Lama "I received my ordination from Kyabjé Ling Rinpoché in the Jokhang in Lhasa."[65] There was very limited Chinese involvement at this time.[66] The family of the 14th Dalai Lama was elevated to the highest stratum of the Tibetan aristocracy and acquired land and serf holdings, as with the families of previous Dalai Lamas.[67]

In 1959, at the age of 23, he took his final examination at Lhasa's Jokhang Temple during the annual Monlam Prayer Festival.[i][69] He passed with honours and was awarded the Lharampa degree, the highest-level geshe degree, roughly equivalent to a doctorate in Buddhist philosophy.[70][71]

According to the Dalai Lama, he had a succession of tutors in Tibet including Reting Rinpoche, Tathag Rinpoche, Ling Rinpoche and lastly Trijang Rinpoche, who became junior tutor when he was 19[72] At the age of 11 he met the Austrian mountaineer Heinrich Harrer, who became his videographer and tutor about the world outside Lhasa. The two remained friends until Harrer's death in 2006.[73]

Life as the Dalai Lama

[edit]

Historically the Dalai Lamas or their regents held political and religious leadership over Tibet from Lhasa with varying degrees of influence depending on the regions of Tibet and periods of history. This began with the 5th Dalai Lama's rule in 1642 and lasted until the 1950s (except for 1705–1750), during which period the Dalai Lamas headed the Tibetan government or Ganden Phodrang. Until 1912 however, when the 13th Dalai Lama declared the complete independence of Tibet, their rule was generally subject to patronage and protection of firstly Mongol kings (1642–1720) and then the Manchu-led Qing dynasty (1720–1912).[74]

During the Dalai Lama's recognition process, the cultural Anthropologist Melvyn Goldstein writes that "everything the Tibetans did during the selection process was designed to prevent China from playing any role".[12][75]

Afterwards in 1939, at the age of four, the Dalai Lama was taken in a procession of lamas to Lhasa. Former British officials stationed in India and Tibet recalled that envoys from Britain and China were present at the Dalai Lama's enthronement in February 1940. According to Basil Gould, the Chinese representative Wu Chunghsin was reportedly unhappy about the position he had during the ceremony. Afterward an article appeared in the Chinese press falsely claiming that Wu personally announced the installation of the Dalai Lama, who supposedly prostrated himself to Wu in gratitude.[76][77]

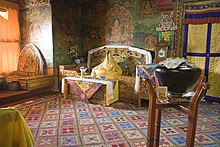

After his enthronement, the Dalai Lama's childhood was then spent between the Potala Palace and Norbulingka, his summer residence, both of which are now UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Chiang Kai Shek ordered Ma Bufang to put his Muslim soldiers on alert for an invasion of Tibet in 1942.[78] Ma Bufang complied, and moved several thousand troops to the border with Tibet.[79] Chiang also threatened the Tibetans with aerial bombardment if they worked with the Japanese. Ma Bufang attacked the Tibetan Buddhist Tsang monastery in 1941.[80] He also constantly attacked the Labrang monastery.[81]

In October 1950 the army of the People's Republic of China marched to the edge of the Dalai Lama's territory and sent a delegation after defeating a legion of the Tibetan army in warlord-controlled Kham. On 17 November 1950, at the age of 15, the 14th Dalai Lama assumed full temporal (political) power as ruler of Tibet.[9]

Cooperation and conflicts with the People's Republic of China

[edit]

The Dalai Lama's formal rule as head of the government in Tibet was brief although he was enthroned as spiritual leader on 22 February 1940. When Chinese cadres entered Tibet in 1950, with a crisis looming, the Dalai Lama was asked to assume the role of head of state at the age of 15, which he did on 17 November 1950. Customarily the Dalai Lama would typically assume control at about the age of 20.[82]

He sent a delegation to Beijing, which ratified the Seventeen Point Agreement without his authorisation in 1951.[83] The Dalai Lama believes the draft agreement was written by China. Tibetan representatives were not allowed to suggest any alterations and China did not allow the Tibetan representatives to communicate with the Tibetan government in Lhasa. The Tibetan delegation was not authorised by Lhasa to sign, but ultimately submitted to pressure from the Chinese to sign anyway, using seals specifically made for the purpose.[84] The Seventeen Point Agreement recognised Chinese sovereignty over Tibet, but China allowed the Dalai Lama to continue to rule Tibet internally, and it allowed the system of feudal peasantry to persist.[85]

Scholar Robert Barnett wrote of the serfdom controversy: "So even if it were agreed that serfdom and feudalism existed in Tibet, this would be little different other than in technicalities from conditions in any other 'premodern' peasant society, including most of China at that time. The power of the Chinese argument therefore lies in its implication that serfdom, and with it feudalism, is inseparable from extreme abuse. Evidence to support this linkage has not been found by scholars other than those close to Chinese governmental circles. Goldstein, for example, notes that although the system was based on serfdom, it was not necessarily feudal, and he refutes any automatic link with extreme abuse."[86]

The 19-year-old Dalai Lama toured China for almost a year from 1954 to 1955, meeting many of the revolutionary leaders and the top echelon of the Chinese communist leadership who created modern China. He learned Chinese and socialist ideals, as explained by his Chinese hosts, on a tour of China showcasing the benefits of socialism and the effective governance provided to turn the large, impoverished nation into a modern and egalitarian society, which impressed him.[87] In September 1954, he went to the Chinese capital to meet Chairman Mao Zedong with the 10th Panchen Lama and attend the first session of the National People's Congress as a delegate, primarily discussing China's constitution.[88][89] On 27 September 1954, the Dalai Lama was selected as a Vice-chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress,[90][91] a post he officially held until 1964.[92][93]

In 1956, on a trip to India to celebrate the Buddha's Birthday, the Dalai Lama asked the Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, if he would allow him political asylum should he choose to stay. Nehru discouraged this as a provocation against peace, and reminded him of the Indian Government's non-interventionist stance agreed upon with its 1954 treaty with China.[71]

Long called a "splittist" and "traitor" by China,[96] the Dalai Lama has attempted formal talks over Tibet's status in China.[97] In 2019, after the United States passed a law requiring the US to deny visas to Chinese officials in charge of implementing policies that restrict foreign access to Tibet, the US Ambassador to China "encouraged the Chinese government to engage in substantive dialogue with the Dalai Lama or his representatives, without preconditions, to seek a settlement that resolves differences".[98]

The Chinese Foreign Ministry has warned the US and other countries to "shun" the Dalai Lama during visits and often uses trade negotiations and human rights talks as an incentive to do so.[99][100][101][102] China sporadically bans images of the Dalai Lama and arrests citizens for owning photos of him in Tibet.[103][104][105] Tibet Autonomous Region government job candidates must strongly denounce the Dalai Lama, as announced on the Tibet Autonomous Region government's online education platform,

The Dalai Lama is a target of Chinese state sponsored hacking. Security experts claim "targeting Tibetan activists is a strong indicator of official Chinese government involvement" since economic information is the primary goal of private Chinese hackers.[107] In 2009 the personal office of the Dalai Lama asked researchers at the Munk Center for International Studies at the University of Toronto to check its computers for malicious software. This led to uncovering GhostNet, a large-scale cyber spying operation which infiltrated at least 1,295 computers in 103 countries, including embassies, foreign ministries, other government offices, and organisations affiliated with the Dalai Lama in India, Brussels, London and New York, and believed to be focusing on the governments of South and Southeast Asia.[108][109][110]

A second cyberspy network, Shadow Network, was discovered by the same researchers in 2010. Stolen documents included a year's worth of the Dalai Lama's personal email, and classified government material relating to India, West Africa, the Russian Federation, the Middle East, and NATO. "Sophisticated" hackers were linked to universities in China, Beijing again denied involvement.[111][112] Chinese hackers posing as The New York Times, Amnesty International and other organisation's reporters targeted the private office of the Dalai Lama, Tibetan Parliament members, and Tibetan nongovernmental organisations, among others, in 2019.[113]

Exile to India

[edit]

At the outset of the 1959 Tibetan uprising, fearing for his life, the Dalai Lama and his retinue fled Tibet with the help of the CIA's Special Activities Division,[115] crossing into India on 30 March 1959, reaching Tezpur in Assam on 18 April.[116] Some time later he set up the Government of Tibet in Exile in Dharamshala, India,[117] which is often referred to as "Little Lhasa". After the founding of the government in exile he re-established the approximately 80,000 Tibetan refugees who followed him into exile in agricultural settlements.[70]

He created a Tibetan educational system in order to teach the Tibetan children the language, history, religion, and culture. The Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts was established[70] in 1959 and the Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies[70] became the primary university for Tibetans in India in 1967. He supported the refounding of 200 monasteries and nunneries in an attempt to preserve Tibetan Buddhist teachings and the Tibetan way of life.

The Dalai Lama appealed to the United Nations on the rights of Tibetans. This appeal resulted in three resolutions adopted by the General Assembly in 1959, 1961, and 1965,[70] all before the People's Republic was allowed representation at the United Nations.[118] The resolutions called on China to respect the human rights of Tibetans.[70] In 1963, he promulgated a democratic constitution which is based upon the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, creating an elected parliament and an administration to champion his cause. In 1970, he opened the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives in Dharamshala which houses over 80,000 manuscripts and important knowledge resources related to Tibetan history, politics and culture. It is considered one of the most important institutions for Tibetology in the world.[119]

In 2016, there were demands from Indian citizens and politicians of different political parties to confer the Dalai Lama the prestigious Bharat Ratna, the highest civilian honour of India, which has only been awarded to a non-Indian citizen twice in its history.[120]

In 2021, it was revealed that the Dalai Lama's inner circle were listed in the Pegasus project data as having been targeted with spyware on their phones. Analysis strongly indicates potential targets were selected by the Indian government.[121][122]

International advocacy

[edit]

At the Congressional Human Rights Caucus in 1987 in Washington, D.C., the Dalai Lama gave a speech outlining his ideas for the future status of Tibet. The plan called for Tibet to become a democratic "zone of peace" without nuclear weapons, and with support for human rights.[citation needed] The plan would come to be known as the "Strasbourg proposal," because the Dalai Lama expanded on the plan at Strasbourg on 15 June 1988. There, he proposed the creation of a self-governing Tibet "in association with the People's Republic of China." This would have been pursued by negotiations with the PRC government, but the plan was rejected by the Tibetan Government-in-Exile in 1991.[123] The Dalai Lama has indicated that he wishes to return to Tibet only if the People's Republic of China agrees not to make any precondition for his return.[124] In the 1970s, the Paramount leader Deng Xiaoping set China's sole return requirement to the Dalai Lama as that he "must [come back] as a Chinese citizen ... that is, patriotism".[125]

The Dalai Lama celebrated his 70th birthday on 6 July 2005. About 10,000 Tibetan refugees, monks and foreign tourists gathered outside his home. Patriarch Alexius II of the Russian Orthodox Church alleged positive relations with Buddhists. However, later that year, the Russian state prevented the Dalai Lama from fulfilling an invitation to the traditionally Buddhist republic of Kalmykia.[126] The President of the Republic of China (Taiwan), Chen Shui-bian, attended an evening celebrating the Dalai Lama's birthday at the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall in Taipei.[127] In October 2008 in Japan, the Dalai Lama addressed the 2008 Tibetan violence that had erupted and that the Chinese government accused him of fomenting. He responded that he had "lost faith" in efforts to negotiate with the Chinese government, and that it was "up to the Tibetan people" to decide what to do.[128]

During his visit to Taiwan after Typhoon Morakot 30 Taiwanese indigenous peoples protested against the Dalai Lama and denounced it as politically motivated.[129][130][131][132]

The Dalai Lama is an advocate for a world free of nuclear weapons, and serves on the Advisory Council of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation.

The Dalai Lama has voiced his support for the Campaign for the Establishment of a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly, an organisation which campaigns for democratic reformation of the United Nations, and the creation of a more accountable international political system.[133]

Teaching activities, public talks

[edit]

Despite becoming 80 years old in 2015, he maintains a busy international lecture and teaching schedule.[134] His public talks and teachings are usually webcast live in multiple languages, via an inviting organisation's website, or on the Dalai Lama's own website. Scores of his past teaching videos can be viewed there, as well as public talks, conferences, interviews, dialogues and panel discussions.[135]

The Dalai Lama's best known teaching subject is the Kalachakra tantra which, as of 2014, he had conferred a total of 33 times,[136] most often in India's upper Himalayan regions but also in the Western world.[137] The Kalachakra (Wheel of Time) is one of the most complex teachings of Buddhism, sometimes taking two weeks to confer, and he often confers it on very large audiences, up to 200,000 students and disciples at a time.[137][138]

The Dalai Lama is the author of numerous books on Buddhism,[139] many of them on general Buddhist subjects but also including books on particular topics like Dzogchen,[140] a Nyingma practice.

In his essay "The Ethic of Compassion" (1999), the Dalai Lama expresses his belief that if we only reserve compassion for those that we love, we are ignoring the responsibility of sharing these characteristics of respect and empathy with those we do not have relationships with, which cannot allow us to "cultivate love." He elaborates upon this idea by writing that although it takes time to develop a higher level of compassion, eventually we will recognise that the quality of empathy will become a part of life and promote our quality as humans and inner strength.[141]

He frequently accepts requests from students to visit various countries worldwide in order to give teachings to large Buddhist audiences, teachings that are usually based on classical Buddhist texts and commentaries,[142] and most often those written by the 17 pandits or great masters of the Nalanda tradition, such as Nagarjuna,[143][144] Kamalashila,[145][146] Shantideva,[147] Atisha,[148] Aryadeva[149] and so on.

The Dalai Lama refers to himself as a follower of these Nalanda masters,[150] in fact he often asserts that 'Tibetan Buddhism' is based on the Buddhist tradition of Nalanda monastery in ancient India,[151] since the texts written by those 17 Nalanda pandits or masters, to whom he has composed a poem of invocation,[152] were brought to Tibet and translated into Tibetan when Buddhism was first established there and have remained central to the teachings of Tibetan Buddhism ever since.[153]

As examples of other teachings, in London in 1984 he was invited to give teachings on the Twelve Links of Dependent Arising, and on Dzogchen, which he gave at Camden Town Hall; in 1988 he was in London once more to give a series of lectures on Tibetan Buddhism in general, called 'A Survey of the Paths of Tibetan Buddhism'.[154] Again in London in 1996 he taught the Four Noble Truths, the basis and foundation of Buddhism accepted by all Buddhists, at the combined invitation of 27 different Buddhist organisations of all schools and traditions belonging to the Network of Buddhist Organisations UK.[155]

In India, the Dalai Lama gives religious teachings and talks in Dharamsala[148] and numerous other locations including the monasteries in the Tibetan refugee settlements,[142] in response to specific requests from Tibetan monastic institutions, Indian academic, religious and business associations, groups of students and individual/private/lay devotees.[156] In India, no fees are charged to attend these teachings since costs are covered by requesting sponsors.[142] When he travels abroad to give teachings there is usually a ticket fee calculated by the inviting organisation to cover the costs involved[142] and any surplus is normally to be donated to recognised charities.[157]

He has frequently visited and lectured at colleges and universities,[158][159][160] some of which have conferred honorary degrees upon him.[161][162]

Dozens of videos of recorded webcasts of the Dalai Lama's public talks on general subjects for non-Buddhists like peace, happiness and compassion, modern ethics, the environment, economic and social issues, gender, the empowerment of women and so forth can be viewed in his office's archive.[163]

Interfaith dialogue

[edit]The Dalai Lama met Pope Paul VI at the Vatican in 1973. He met Pope John Paul II in 1980, 1982, 1986, 1988, 1990, and 2003. In 1990, he met a delegation of Jewish teachers in Dharamshala for an extensive interfaith dialogue.[164] He has since visited Israel three times, and in 2006 met the Chief Rabbi of Israel. In 2006, he met Pope Benedict XVI privately. He has met the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr. Robert Runcie, and other leaders of the Anglican Church in London, Gordon B. Hinckley, who at the time was the president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as well as senior Eastern Orthodox Church, Muslim, Hindu, Jewish, and Sikh officials.

In 1996 and 2002, he participated in the first two Gethsemani Encounters hosted by the Monastic Interreligious Dialogue at the Abbey of Our Lady of Getshemani, where Thomas Merton, whom the Dalai Lama had met in the late 1960s, had lived.[165][166] He is also a member of the Board of World Religious Leaders as part of The Elijah Interfaith Institute[167] and participated in the Third Meeting of the Board of World Religious Leaders in Amritsar, India, on 26 November 2007 to discuss the topic of Love and Forgiveness.[168] In 2009, the Dalai Lama inaugurated an interfaith "World Religions-Dialogue and Symphony" conference at Gujarat's Mahuva religions, according to Morari Bapu.[169][170]

In 2010, the Dalai Lama, joined by a panel of scholars, launched the Common Ground Project,[171] in Bloomington, Indiana (USA),[172] which was planned by himself and Prince Ghazi bin Muhammad of Jordan during several years of personal conversations. The project is based on the book Common Ground between Islam and Buddhism.[173]

In 2019, the Dalai Lama fully sponsored the first-ever 'Celebrating Diversity in the Muslim World' conference in New Delhi on behalf of the Muslims of Ladakh.[174]

Interest in science, and Mind and Life Institute

[edit]

The Dalai Lama's lifelong interest in science[175][176] and technology[177] dates from his childhood in Lhasa, Tibet, when he was fascinated by mechanical objects like clocks, watches, telescopes, film projectors, clockwork soldiers[177] and motor cars,[178] and loved to repair, disassemble and reassemble them.[175] Once, observing the Moon through a telescope as a child, he realised it was a crater-pocked lump of rock and not a heavenly body emitting its own light as Tibetan cosmologists had taught him.[175] He has also said that had he not been brought up as a monk he would probably have been an engineer.[179] On his first trip to the west in 1973 he asked to visit Cambridge University's astrophysics department in the UK and he sought out renowned scientists such as Sir Karl Popper, David Bohm and Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker,[178] who taught him the basics of science.

The Dalai Lama sees important common ground between science and Buddhism in having the same approach to challenge dogma on the basis of empirical evidence that comes from observation and analysis of phenomena.[180]

His growing wish to develop meaningful scientific dialogue to explore the Buddhism and science interface led to invitations for him to attend relevant conferences on his visits to the west, including the Alpbach Symposia on Consciousness in 1983 where he met and had discussions with the late Chilean neuroscientist Francisco J. Varela.[178] Also in 1983, the American social entrepreneur and innovator R. Adam Engle,[181] who had become aware of the Dalai Lama's deep interest in science, was already considering the idea of facilitating for him a serious dialogue with a selection of appropriate scientists.[182] In 1984 Engle formally offered to the Dalai Lama's office to organise a week-long, formal dialogue for him with a suitable team of scientists, provided that the Dalai Lama would wish to fully participate in such a dialogue. Within 48 hours the Dalai Lama confirmed to Engle that he was "truly interested in participating in something substantial about science" so Engle proceeded with launching the project.[183] Francisco Varela, having heard about Engle's proposal, then called him to tell him of his earlier discussions with the Dalai Lama and to offer his scientific collaboration to the project.[183] Engle accepted, and Varela assisted him to assemble his team of six specialist scientists for the first 'Mind and Life' dialogue on the cognitive sciences,[184] which was eventually held with the Dalai Lama at his residence in Dharamsala in 1987.[178][183] This five-day event was so successful that at the end the Dalai Lama told Engle he would very much like to repeat it again in the future.[185] Engle then started work on arranging a second dialogue, this time with neuroscientists in California, and the discussions from the first event were edited and published as Mind and Life's first book, "Gentle Bridges: Conversations with the Dalai Lama on the Sciences of Mind".[186]

As Mind and Life Institute's remit expanded, Engle formalised the organisation as a non-profit foundation after the third dialogue, held in 1990, which initiated the undertaking of neurobiological research programmes in the United States under scientific conditions.[185] Over the following decades, as of 2014 at least 28 dialogues between the Dalai Lama and panels of various world-renowned scientists have followed, held in various countries and covering diverse themes, from the nature of consciousness to cosmology and from quantum mechanics to the neuroplasticity of the brain.[187] Sponsors and partners in these dialogues have included the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,[188] Johns Hopkins University,[189] the Mayo Clinic,[190] and Zurich University.[191]

Apart from time spent teaching Buddhism and fulfilling responsibilities to his Tibetan followers, the Dalai Lama has probably spent, and continues to spend, more of his time and resources investigating the interface between Buddhism and science through the ongoing series of Mind and Life dialogues and its spin-offs than on any other single activity.[177] As the institute's Cofounder and the Honorary chairman he has personally presided over and participated in all its dialogues, which continue to expand worldwide.[192]

These activities have given rise to dozens of DVD sets of the dialogues and books he has authored on them such as Ethics for the New Millennium and The Universe in a Single Atom, as well as scientific papers and university research programmes.[193] On the Tibetan and Buddhist side, science subjects have been added to the curriculum for Tibetan monastic educational institutions and scholarship.[194] On the Western side, university and research programmes initiated by these dialogues and funded with millions of dollars in grants from the Dalai Lama Trust include the Emory-Tibet Partnership,[195] Stanford School of Medicine's Centre for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education (CCARES)[196] and the Centre for Investigating Healthy Minds,[197] amongst others.

In 2019, Emory University's Center for Contemplative Sciences and Compassion-Based Ethics, in partnership with The Dalai Lama Trust and the Vana Foundation of India, launched an international SEE Learning (Social, Emotional and Ethical Learning) program in New Delhi, India, a school curriculum for all classes from kindergarten to Std XII that builds on psychologist Daniel Goleman's work on emotional intelligence in the early 1990s. SEE learning focuses on developing critical thinking, ethical reasoning and compassion and stresses on commonalities rather than on the differences.[198][199][200][201]

In particular, the Mind and Life Education Humanities & Social Sciences initiatives have been instrumental in developing the emerging field of Contemplative Science, by researching, for example, the effects of contemplative practice on the human brain, behaviour and biology.[193]

In his 2005 book The Universe in a Single Atom and elsewhere, and to mark his commitment to scientific truth and its ultimate ascendancy over religious belief, unusually for a major religious leader the Dalai Lama advises his Buddhist followers: "If scientific analysis were conclusively to demonstrate certain claims in Buddhism to be false, then we must accept the findings of science and abandon those claims."[202] He has also cited examples of archaic Buddhist ideas he has abandoned himself on this basis.[175][203]

These activities have even had an impact in the Chinese capital. In 2013 an 'academic dialogue' with a Chinese scientist, a Tibetan 'living Buddha' and a professor of Religion took place in Beijing. Entitled "High-end dialogue: ancient Buddhism and modern science" it addressed the same considerations that interest the Dalai Lama, described as 'discussing about the similarities between Buddhism and modern science'.[204]

Personal meditation practice

[edit]The Dalai Lama uses various meditation techniques, including analytic meditation and emptiness meditation.[205] He has said that the aim of meditation is

Social stances

[edit]Tibetan independence

[edit]Despite initially advocating for Tibetan independence from 1961 to 1974, the Dalai Lama no longer supports it. Instead he advocates for more meaningful autonomy for Tibetans within the People's Republic of China.[208] This approach is known as the "Middle Way". In 2005, the 14th Dalai Lama emphasized that Tibet is a part of China, and Tibetan culture and Buddhism are part of Chinese culture. [209] In a speech at Kolkata in 2017, the Dalai Lama stated that Tibetans wanted to stay with China and they did not desire independence. He said that he believed that China after opening up, had changed 40 to 50 per cent of what it was earlier, and that Tibetans wanted to get more development from China.[210] In October 2020, the Dalai Lama stated that he did not support Tibetan independence and hoped to visit China as a Nobel Prize winner. He said "I prefer the concept of a 'republic' in the People's Republic of China. In the concept of republic, ethnic minorities are like Tibetans, The Mongols, Manchus, and Xinjiang Uyghurs, we can live in harmony".[211]

Abortion

[edit]The Dalai Lama has said that, from the perspective of the Buddhist precepts, abortion is an act of killing.[214] In 1993, he clarified a more nuanced position, stating, "... it depends on the circumstances. If the unborn child will be retarded or if the birth will create serious problems for the parent, these are cases where there can be an exception. I think abortion should be approved or disapproved according to each circumstance."[215]

Death penalty

[edit]The Dalai Lama has repeatedly expressed his opposition to the death penalty, saying that it contradicts the Buddhist philosophy of non-violence and that it expresses anger, not compassion.[216] During a 2005 visit to Japan, a country which has the death penalty, the Dalai Lama called for the abolition of the death penalty and said in his address, "Criminals, people who commit crimes, usually society rejects these people. They are also part of society. Give them some form of punishment to say they were wrong, but show them they are part of society and can change. Show them compassion."[217] The Dalai Lama has also praised U.S. states that have abolished the death penalty.[218]

Democracy, nonviolence, religious harmony, and Tibet's relationship with India

[edit]

The Dalai Lama says that he is active in spreading India's message of nonviolence and religious harmony throughout the world.[219] "I am the messenger of India's ancient thoughts the world over." He has said that democracy has deep roots in India. He says he considers India the master and Tibet its disciple, as great scholars went from India to Tibet to teach Buddhism. He has noted that millions of people lost their lives in violence and the economies of many countries were ruined due to conflicts in the 20th century. "Let the 21st century be a century of tolerance and dialogue."[220]

The Dalai Lama has also critiqued proselytisation and certain types of conversion, believing the practices to be contrary to the fundamental ideas of religious harmony and spiritual practice.[221][222][223][224] He has stated that "It's very important that our religious traditions live in harmony with one another and I don't think proselytizing contributes to this. Just as fighting and killing in the name of religion are very sad, it's not appropriate to use religion as a ground or a means for defeating others."[225] In particular, he has critiqued Christian approaches to conversion in Asia, stating that he has "come across situations where serving the people is a cover for proselytization."[226] The Dalai Lama has labelled such practices counter to the "message of Christ" and has emphasised that such individuals "practice conversion like a kind of war against peoples and cultures."[223] In a statement with Hindu religious leaders, he expressed that he opposes "conversions by any religious tradition using various methods of enticement."[224]

In 1993, the Dalai Lama attended the World Conference on Human Rights and made a speech titled "Human Rights and Universal Responsibility".[227]

In 2001, in response to a question from a Seattle schoolgirl, the Dalai Lama said that it is permissible to shoot someone in self-defense (if the person was "trying to kill you") and he emphasised that the shot should not be fatal.[228]

In 2013, the Dalai Lama criticised Buddhist monks' attacks on Muslims in Myanmar and rejected violence by Buddhists, saying: "Buddha always teaches us about forgiveness, tolerance, compassion. If from one corner of your mind, some emotion makes you want to hit, or want to kill, then please remember Buddha's faith. ... All problems must be solved through dialogue, through talk. The use of violence is outdated, and never solves problems."[229] In May 2013, he said "Really, killing people in the name of religion is unthinkable, very sad."[230] In May 2015, the Dalai Lama called on Myanmar's Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi to do more to help the Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar, and said that he had urged Suu Kyi to address the Rohingyas' plight in two previous private meetings and had been rebuffed.[231]

In 2017, after Chinese dissident and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo died of organ failure while in Chinese government custody, the Dalai Lama said he was "deeply saddened" and that he believed that Liu's "unceasing efforts in the cause of freedom will bear fruit before long."[232]

The Dalai Lama has consistently praised India.[233][234] In December 2018, he said Muslim countries like Bangladesh, Pakistan and Syria should learn about religion from India for peace in the world.[235][236] When asked in 2019 about attacks on the minority community in India including a recent one against a Muslim family in Gurgaon, he said: "There are always a few mischievous people, but that does not mean it a symbol of that nation".[237][238] He reiterated in December 2021 that he thought India was a role model for religious harmony in the world.[239][240]

Diet and animal welfare

[edit]The Dalai Lama advocates compassion for animals and frequently urges people to try vegetarianism or at least reduce their consumption of meat. In Tibet, where historically meat was the most common food, most monks historically have been omnivores, including the Dalai Lamas. The Fourteenth Dalai Lama was raised in a meat-eating family but converted to vegetarianism after arriving in India, where vegetables are much more easily available and vegetarianism is widespread.[242] He spent many years as a vegetarian, but after contracting hepatitis in India and suffering from weakness, his doctors told him to return to eating meat which he now does twice a week.[243] This attracted public attention when, during a visit to the White House, he was offered a vegetarian menu but declined by replying, as he is known to do on occasion when dining in the company of non-vegetarians, "I'm a Tibetan monk, not a vegetarian".[244] His own home kitchen, however, is completely vegetarian.[245]

In 2009, the English singer Paul McCartney wrote a letter to the Dalai Lama inquiring why he was not a vegetarian. As McCartney later told The Guardian, "He wrote back very kindly, saying, 'my doctors tell me that I must eat meat'. And I wrote back again, saying, you know, I don't think that's right. [...] I think now he's vegetarian most of the time. I think he's now being told, the more he meets doctors from the west, that he can get his protein somewhere else. [...] It just doesn't seem right – the Dalai Lama, on the one hand, saying, 'Hey guys, don't harm sentient beings... Oh, and by the way, I'm having a steak.'"[246]

Economics and political stance

[edit]The Dalai Lama has referred to himself as a Marxist and has articulated criticisms of capitalism.[247][248][249]

He reports hearing of communism when he was very young, but only in the context of the destruction of the Mongolian People's Republic. It was only when he went on his trip to Beijing that he learned about Marxist theory from his interpreter Baba Phuntsog Wangyal of the Tibetan Communist Party.[250] At that time, he reports, "I was so attracted to Marxism, I even expressed my wish to become a Communist Party member," citing his favourite concepts of self-sufficiency and equal distribution of wealth. He does not believe that China implemented "true Marxist policy,"[251] and thinks the historical communist states such as the Soviet Union "were far more concerned with their narrow national interests than with the Workers' International".[252] Moreover, he believes one flaw of historically "Marxist regimes" is that they place too much emphasis on destroying the ruling class, and not enough on compassion.[252] He finds Marxism superior to capitalism, believing the latter is only concerned with "how to make profits," whereas the former has "moral ethics".[253] Stating in 1993:

On India–Pakistan relations, the Dalai Lama in October 2019 said: "There is a difference between Indian and Pakistani Prime Minister's speech at the UN. Indian prime prime minister talks about peace and you know what his Pakistan counterpart said. Getting China's political support is Pakistan's compulsion. But Pakistan also needs India. Pakistani leaders should calm down and think beyond emotions and should follow a realistic approach".[254][255]

Environment

[edit]The Dalai Lama is outspoken in his concerns about environmental problems, frequently giving public talks on themes related to the environment. He has pointed out that many rivers in Asia originate in Tibet, and that the melting of Himalayan glaciers could affect the countries in which the rivers flow.[256] He acknowledged official Chinese laws against deforestation in Tibet, but lamented they can be ignored due to possible corruption.[257] He was quoted as saying "ecology should be part of our daily life";[258] personally, he takes showers instead of baths, and turns lights off when he leaves a room.[256]

Around 2005, he started campaigning for wildlife conservation, including by issuing a religious ruling against wearing tiger and leopard skins as garments.[259][260] The Dalai Lama supports the anti-whaling position in the whaling controversy, but has criticised the activities of groups such as the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society (which carries out acts of what it calls aggressive nonviolence against property).[261] Before the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference, he urged national leaders to put aside domestic concerns and take collective action against climate change.[262]

Sexuality

[edit]The Dalai Lama's stances on topics of sexuality have changed over time.

A monk since childhood, the Dalai Lama has said that sex offers fleeting satisfaction and leads to trouble later, while chastity offers a better life and "more independence, more freedom".[263] He has said that problems arising from conjugal life sometimes even lead to suicide or murder.[264] He has asserted that all religions have the same view about adultery.[265]

In his discussions of the traditional Buddhist view on appropriate sexual behaviour, he explains the concept of "right organ in the right object at the right time," which historically has been interpreted as indicating that oral, manual and anal sex (both homosexual and heterosexual) are not appropriate in Buddhism or for Buddhists. However, he also says that in modern times all common, consensual sexual practices that do not cause harm to others are ethically acceptable and that society should accept and respect people who are gay or transgender from a secular point of view.[266] In a 1994 interview with OUT Magazine, the Dalai Lama clarified his personal opinion on the matter by saying, "If someone comes to me and asks whether homosexuality is okay or not, I will ask 'What is your companion's opinion?' If you both agree, then I think I would say, 'If two males or two females voluntarily agree to have mutual satisfaction without further implication of harming others, then it is okay.'"[267] However, when interviewed by Canadian TV news anchor Evan Solomon on CBC News: Sunday about whether homosexuality is acceptable in Buddhism, the Dalai Lama responded that "it is sexual misconduct".[268]

In his 1996 book Beyond Dogma, he described a traditional Buddhist definition of an appropriate sexual act as follows: "A sexual act is deemed proper when the couples use the organs intended for sexual intercourse and nothing else ... Homosexuality, whether it is between men or between women, is not improper in itself. What is improper is the use of organs already defined as inappropriate for sexual contact."[269] He elaborated in 1997, conceding that the basis of that teaching was unknown to him. He also conveyed his own "willingness to consider the possibility that some of the teachings may be specific to a particular cultural and historic context".[270]

In 2006, the Dalai Lama has expressed concern at "reports of violence and discrimination against" LGBT people and urged "respect, tolerance and the full recognition of human rights for all".[271]

In a 2014 interview with Larry King, the Dalai Lama expressed that same-sex marriage is a personal issue, can be ethically socially accepted, and that he personally accepts it. However, he also stated that if same-sex marriage is in contradiction with one's chosen traditions, then they should not follow it.[272]

Women's rights

[edit]In 2007, he said that the next Dalai Lama could possibly be a woman: "If a woman reveals herself as more useful the lama could very well be reincarnated in this form."[273]

In 2009, on gender equality and sexism, the Dalai Lama proclaimed at the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee: "I call myself a feminist. Isn't that what you call someone who fights for women's rights?" He also said that by nature, women are more compassionate "based on their biology and ability to nurture and birth children". He called on women to "lead and create a more compassionate world," citing the good works of nurses and mothers.[274]

At a 2014 appearance at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences in Mumbai, the Dalai Lama said, "Since women have been shown to be more sensitive to others' suffering, their leadership may be more effective."[275]

In 2015, he said in a BBC interview that if a female succeeded him, "that female must be attractive, otherwise it is not much use," and when asked if he was joking, replied, "No. True!" He followed with a joke about his success being due to his own appearance.[276] His office later released a statement of apology citing the interaction as a translation error.[277]

Health

[edit]In 2013, at the Culture of Compassion event in Derry, Northern Ireland, the Dalai Lama said that "Warm-heartedness is a key factor for healthy individuals, healthy families and healthy communities."[278]

Response to COVID-19

[edit]In a 2020 statement in Time magazine on the COVID-19 pandemic, the Dalai Lama said that the pandemic must be combated with compassion, empirical science, prayer, and the courage of healthcare workers. He emphasised "emotional disarmament" (seeing things with a clear and realistic perspective, without fear or rage) and wrote: "The outbreak of this terrible coronavirus has shown that what happens to one person can soon affect every other being. But it also reminds us that a compassionate or constructive act – whether working in hospitals or just observing social distancing – has the potential to help many."[279]

Immigration

[edit]In September 2018, speaking at a conference in Malmö, Sweden, home to a large immigrant population, the Dalai Lama said "I think Europe belongs to the Europeans," but also that Europe was "morally responsible" for helping "a refugee really facing danger against their life". He stated that Europe has a responsibility to refugees to "receive them, help them, educate them," but that they should aim to return to their places of origin and that "they ultimately should rebuild their own country".[280][281]

Speaking to German reporters in 2016, the Dalai Lama said there are "too many" refugees in Europe, adding that "Europe, for example Germany, cannot become an Arab country." He also said that "Germany is Germany".[282][283]

Retirement and succession plans

[edit]In May 2011, the Dalai Lama retired from the Central Tibetan Administration.[284]

In September 2011, the Dalai Lama issued the following statement concerning his succession and reincarnation:

In October 2011, the Dalai Lama repeated his statement in an interview with Canadian CTV News. He added that Chinese laws banning the selection of successors based on reincarnation will not impact his decisions. "Naturally my next life is entirely up to me. No one else. And also this is not a political matter," he said in the interview. The Dalai Lama also added that he has not decided on whether he would reincarnate or be the last Dalai Lama.[287]

In an interview with the German newspaper Welt am Sonntag published on 7 September 2014 the Dalai Lama stated "the institution of the Dalai Lama has served its purpose," and that "We had a Dalai Lama for almost five centuries. The 14th Dalai Lama now is very popular. Let us then finish with a popular Dalai Lama."[288] In response, the Chinese government said the title of Dalai Lama has been conferred by the central government for hundreds of years and the 14th Dalai Lama has ulterior motives. This was taken by Tibetan activists and The Wire to mean that China will make the Dalai Lama reincarnate no matter what.[289]

Gyatso has also expressed fear that the Chinese government would manipulate any reincarnation selection in order to choose a successor that would go along with their political goals.[290]

Despite the tradition of selecting young children, the 14th Dalai Lama can also name an adult as his next incarnation. Doing so would have the advantage that the successor would not need to spend decades studying Buddhism and can be taken seriously as a leader by the Tibetan diaspora immediately.[291]

CIA Tibetan program

[edit]In October 1998, the Dalai Lama's administration acknowledged that it received $1.7 million a year in the 1960s from the U.S. government through a Central Intelligence Agency program.[292] When asked by CIA officer John Kenneth Knaus in 1995 to comment on the CIA Tibetan program, the Dalai Lama replied that though it helped the morale of those resisting the Chinese, "thousands of lives were lost in the resistance" and further, that "the U.S. Government had involved itself in his country's affairs not to help Tibet but only as a Cold War tactic to challenge the Chinese."[293] As part of the program the Dalai Lama received 180,000 dollars a year from 1959 till 1974 for his own personal use.[294]

His administration's reception of CIA funding has become one of the grounds for some state-run Chinese newspapers to discredit him along with the Tibetan independence movement.[citation needed]

In his autobiography Freedom in Exile, the Dalai Lama criticised the CIA again for supporting the Tibetan independence movement "not because they (the CIA) cared about Tibetan independence, but as part of their worldwide efforts to destabilize all communist governments".[295]

In 1999, the Dalai Lama said that the CIA Tibetan program had been harmful for Tibet because it was primarily aimed at serving American interests, and "once the American policy toward China changed, they stopped their help."[296]

Criticism

[edit]Ties to India

[edit]

The Chinese Communist Party has criticised the 14th Dalai Lama for his close ties with India.[297] In 2008, the Dalai Lama said that Arunachal Pradesh, partially claimed by China, is part of India, citing the disputed 1914 Simla Accord.[298] In 2010 at the International Buddhist Conference in Gujarat, he described himself as a "son of India" and "Tibetan in appearance, but an Indian in spirituality." The newspaper of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, People's Daily, questioned if the Dalai Lama, by considering himself Indian rather than Chinese, is still entitled to represent Tibetans, alluding to the links between Chinese and Tibetan Buddhism and the Dalai Lama siding with India on southern Tibet.[299] Dhundup Gyalpo, the Dalai Lama's eventual secretary in New Delhi, argued that Tibetan and Chinese peoples have no connections apart from a few culinary dishes and that Chinese Buddhists could also be deemed "Indian in spirituality", because both Tibetan and Chinese Buddhism originated from India.[300][301]

Shugden controversy

[edit]Dorje Shugden is an entity in Tibetan Buddhism that, since the 1930s, has become a point of contention over whether to include or exclude certain non-Gelug teachings. After the 1975 publication of the Yellow Book containing stories about Dorje Shugden acting wrathfully against Gelugpas who also practised Nyingma, the 14th Dalai Lama, himself a Gelugpa and advocate of an inclusive approach,[302] publicly renounced the practice of Dorje Shugden.[303][304] Several groups broke away as a result, notably the New Kadampa Tradition (NKT). According to Tibetologists, the Dalai Lama's disapproval has reduced the prevalence of Shugden sects among Tibetans in China and India.[305]

Shugden devotees have since complained about being ostracized when trying to get jobs or receive services. The Dalai Lama's supporters expressed that any discrimination is neither systematic nor encouraged by him.[305] Some Shugden movements such as the NKT have organised demonstrations as a form of protest.[306] One group, the International Shugden Community (ISC), came under scrutiny from Reuters in 2015. While the journalists found "no independent evidence of direct Chinese financing," they reported that Beijing had "thrown its weight behind Shugden devotees" and the ISC became China's instrument to discredit the Dalai Lama.[305] The group disbanded in 2016.[307] That same year, the Dalai Lama re-stated his position on Dorje Shugden, saying "I've encouraged people not to do the practice, but I haven't said that no one can do it."[308][309] His office said that there was no ban or discrimination against Shugden worshippers.[310]

Comments on a potential female Dalai Lama